Which Buildings are the Highest Carbon Emitters?

I recently had the opportunity to join a technical conference panel about electrification at FERC, where we primarily addressed the market and grid implications of building and transportation electrification.

In my pre-panel comments to FERC, I did not have a chance to address an important aspect of building decarbonization: the on-site carbon emissions vary a lot between buildings.

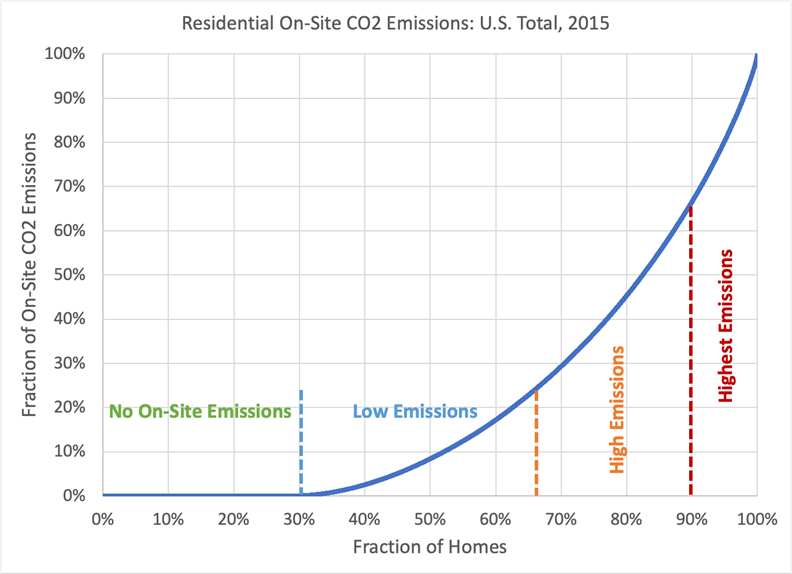

This is not necessarily news: some buildings are all-electric, with no on-site emissions, while others burn extensive amounts of heating oil or natural gas all winter. Nonetheless, it is common to see policy objectives stated in terms of the number of buildings to be electrified, or the number of heat pumps to be deployed. The actual impact of that electrification depends on which buildings modernize their systems. As a result, the actual shape of the emissions distributions provides an extra level of insight, as pictured below.

I’ve parsed data from EIA’s 2015 Residential Energy Consumption Survey, and here’s what I found:

- The highest-emitting 10 percent of homes are responsible for one-third of total on-site emissions in the United States. The highest-emitting third of buildings are responsible for three-quarters of emissions. (It’s not quite 80/20, but it’s closer than you might think!) Meanwhile, about 30 percent of homes were already emission-free on site in 2015.

- While there is no one characteristic that links all the highest-emitting homes, they are more likely than average to use heating oil, be located in cold climates (or at least, north of the Mason-Dixon line), and tend to be larger and/or older than the average home.

-

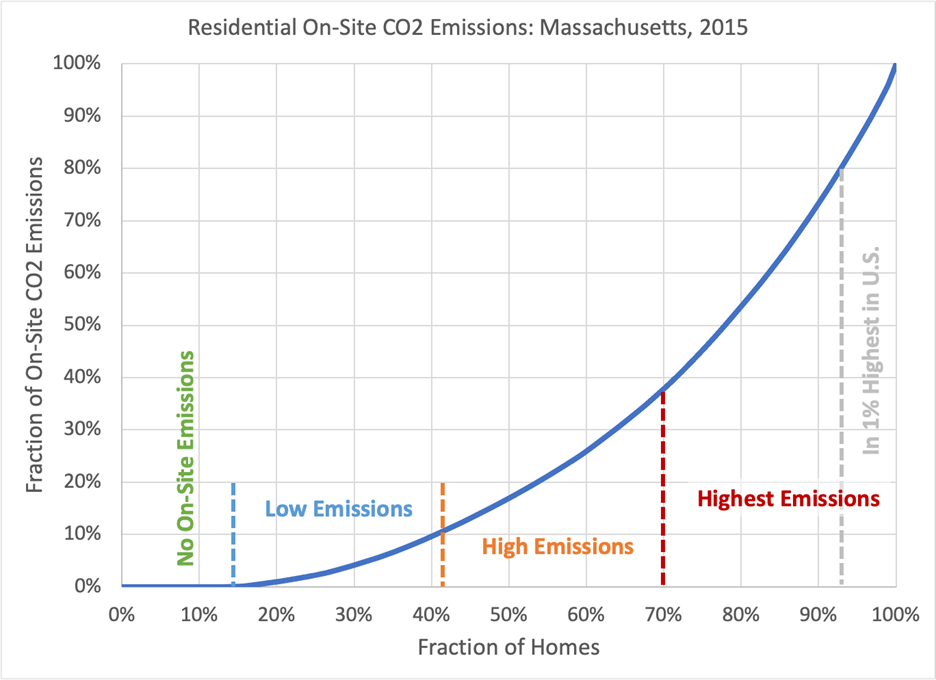

Zooming in on Synapse’s home state of Massachusetts, we can see these trends play out below. Here, 30 percent of homes are in the highest-emitting national group, and 8 percent of the state’s homes are in the top 1 percent of U.S. residential emitters. These super-emitters are responsible for 20 percent of the state’s residential on-site emissions. Half of the residential sector’s on-site emissions come from just 22 percent of homes.

- The highest-emitting homes in Massachusetts have much in common with their national counterparts: they are larger in size and more likely to be heated with oil. They are also more likely to be owner-occupied, although there are poorly performing homes with low- and moderate-income residents in this group as well. Nonetheless, targeting policies and programs exclusively based on emissions would risk creating programs that exacerbate, rather than remedy, inequities.

Decarbonization policies should take a two-pronged approach, with a focus on (1) high-emitting homes and (2) low- and moderate-income residents and renters. To target programs, gas utilities and fuel dealers know who their highest-consuming customers are, and utilities and state programs already have programs for low-income heating and energy assistance.

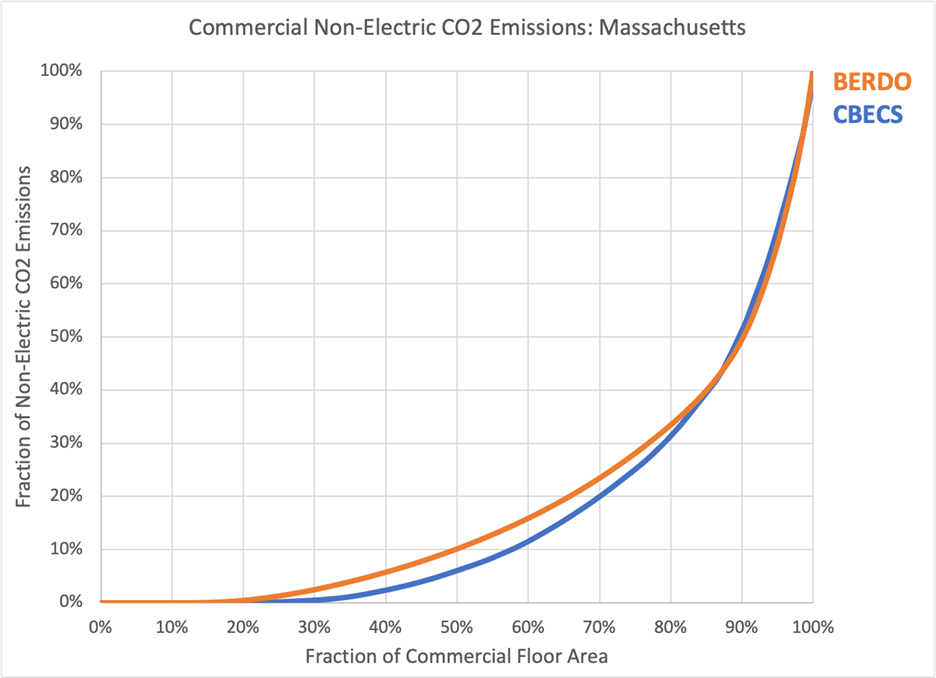

Commercial buildings are even more diverse than homes, so it is not surprising that the comparable distributions of non-electric emissions across buildings are even wider. Hospitals and laboratory buildings, for example, are much more emissions-intensive than warehouses or offices. My colleagues and I examined the distributions for Boston (derived from the data required by Boston’s energy reporting and disclosure ordinance) and Massachusetts (derived from the EIA’s Commercial Building Energy Consumption Survey), and they are shown here:

Both sources agree that 20 percent of the floor area is responsible for almost 70 percent of on-site emissions. In Boston, these high-emitters will need to address their emissions to comply with the proposed building performance standard. Given the size of many of the largest emitters, there are a limited number of building owners and decision-makers in this highest-emitting group. This means that decarbonization programs that use direct and sustained engagement with this relatively small group could have an enormous impact on the state’s emissions.